Welcome to the Father Ignatius Memorial Trust website

The Monastery

The Monastery was founded in 1870 by Fr Ignatius with the aim of restoring monastic life to the Church of England, and it remained in monastic use for over forty years. Eric Gill, the sculptor and typographer, lived there from 1924 to 1928. It is now a private home.

The Pilgrimage

The next Trust Pilgrimage will be on Saturday September 5th 2026. Background information is given on the Pilgrimage page, and more details will be available in the 2026 Trust Newsletter and on our Facebook page in due course.

The Trust

The Trust’s objectives include the care of Ignatius’ ruined abbey church, and the nearby Wayside Calvary and statue of Our Lady, as places of pilgrimage, prayer and worship. Although the church is is now structurally unsound and unsafe for public entry, it remains a focus of the annual pilgrimage.

The Trust Archive

There is a collection of Father Ignatius Memorial Trust archive material at Abergavenny Museum. We have also made some documents and articles available on the website on the Documents page.

How you can help

We aim to keep the memory of Ignatius alive and to continue the annual Pilgrimage. You are warmly invited to make a donation and to become a Friend of the Father Ignatius Memorial Trust by subscribing to the Trust Newsletter.

(See the Help Us page).

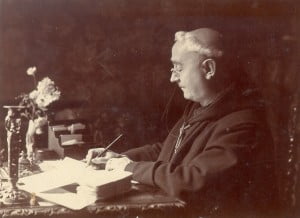

Father Ignatius of Llanthony

Fr Ignatius OSB (Revd. Joseph Leycester Lyne, 1837-1908) was a prominent figure in the Catholic Revival which swept the 19th century Church of England. As a young man he resolved to restore to it the monastic life lost at the Reformation, and devoted the rest of his life to this aim.

Learn more

Father Ignatius Memorial Trust

Fr Ignatius (Revd. Joseph Leycester Lyne,1837-1908) was a prominent figure in the Catholic Revival which swept the 19th century Church of England.